Impact of deep brain stimulation surgery on speech and swallowing in patients with essential tremor

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The ventral intermediate nucleus (VIM) of the thalamus is the typical target of deep brain stimulation (DBS) for controlling tremor in essential tremor (ET). It remains unclear whether the outcomes are significantly different on speech and/or swallowing functions. This study was to compare speech and swallowing outcomes in patients with ET without VIM DBS, and those with unilateral/bilateral VIM DBS.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of 133 patients with the diagnosis of ET. We analyzed the clinical speech and swallowing evaluations, and compared outcomes across four ‘DBS disposition’ groupings: no DBS, left, right, or bilateral VIM DBS.

Results

Speech function was worse in bilateral group versus no DBS and unilateral groups. Orofacial (p=0.000), rate (p=0.001), and prosody (p=0.003) were significantly different between groups. No DBS and unilateral groups demonstrated either no dysarthria or mild hyperkinetic dysarthria versus exhibiting higher rates of dysarthria including an ataxic component in bilateral group. Bilateral group showed more impaired swallowing severity versus no DBS and unilateral groups, however, these differences were not statistically significant.

Conclusions

The results demonstrated speech and swallowing changes in the ET patient population after VIM DBS. This data provides support for further study in order to better understand the speech and/or swallowing changes that may occur with VIM DBS.

INTRODUCTION

Essential tremor (ET) is the most common movement disorder and is characterized by postural and kinetic tremors [1–3], predominately in the upper limbs, head, face and voice [3,4]. Approximately 50% of patients show benefits from medication, but when medication is ineffective or has lost effect in reducing the tremor, many patients opt for deep brain stimulation (DBS) [3,5]. For ET, the ventral intermediate nucleus (VIM) of the thalamus is a common DBS target [5].

While tremors in ET occur most commonly in the distal upper limbs, they can occur in midline structures (e.g., head, voice, face, and trunk) [6–9]. When tremors occur in these midline structures, they manifest mainly as head and/or voice tremors [6–9], resulting in hyperkinetic dysarthria. Unlike the classic distal upper extremity tremor, these midline tremors usually persist post-DBS surgery [7–10]. Moreover, deficits in speech function can lower quality of life and impact social functioning [1]. There are several studies that have investigated speech function after VIM DBS surgery in ET, but the results of these studies are inconsistent [11,12]. For example, one study reported on a single case of bilateral DBS and vocal tremor [13]. Researchers used kinesthetic and acoustic measurements to identify improvement of tremor post-bilateral VIM DBS, and the result showed that the rate of F0 modulation and overall tremor severity were reduced. Erickson-DiRenzo et al. [14] also identified that the rate of intensity modulation, extent of fundamental frequency modulation, and perceptual rating of essential vocal tremor severity were significantly reduced during intra-operational VIM DBS condition versus pre-operational VIM DBS condition in seven patients with ET.

On the other hand, Becker et al. [1] conducted a study of speech function in 16 ET patients after bilateral VIM DBS. The authors evaluated speech under four different conditions: DBS off, unilateral left and right DBS on, and bilateral DBS on. Their findings indicate worsening of speech function in the DBS on conditions as compared to the DBS off condition, with worse overall performance in the bilateral on condition. The later study of Becker et al. [15] also identified that 13 patients with ET showed longer syllable durations and a reduction in articulation rate after VIM DBS surgery compared to preoperative condition. Mücke et al. [11] investigated both acoustic and articulatory patterns with Electromagnetic Articulography in 12 patients with ET in VIM DBS on versus DBS off condition. All patients had reduced articulatory precision and slowness, however, in DBS on condition, there was further deterioration of articulatory precision and slowness.

Swallowing dysfunction is also associated with reduced quality of life and other negative health outcomes, such as dehydration and lung infection. Lapa et al. [16] retrospectively investigated swallowing function with flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) in 12 patients with ET after bilateral VIM DBS in the on and off conditions. Results showed that all patients self-reported swallowing problems during the course of DBS treatment. Dysphagia was present in all patients during DBS on condition, and there was a statistically significant improvement of swallowing function to all patients in DBS off condition. In other words, VIM DBS seemed to induce dysphagia as an adverse effect. However, little research has been systematically investigated yet and it is not clear whether VIM DBS affects swallowing function in ET patients.

The goal of this study was to further specify potential impacts to both speech and swallowing functions in people with ET and VIM DBS surgery. To date, speech and swallowing effects from VIM DBS surgery in patients with ET have been mostly investigated with small sample sizes comparing pre-and post-DBS conditions, making it difficult to generalize the implications for speech and swallowing. However, in this study, we collected retrospective data from a larger sample in order to better characterize the impact of both unilateral and bilateral VIM DBS on speech and swallowing function comparing groups of patients with and without DBS surgery. We divided patients with ET into four groups: 1) no DBS, 2) left VIM DBS, 3) right VIM DBS, and 4) bilateral VIM DBS. We aimed to determine whether unilateral versus bilateral VIM DBS differentially impact speech and swallow outcomes. Based on the previous studies [1,11,15,16], we hypothesized that both speech and swallowing functions would be worse when VIM DBS is present. Further, we hypothesized those with bilateral VIM DBS would have significantly worse measures of speech and swallowing function versus unilateral VIM DBS.

METHODS

Participants

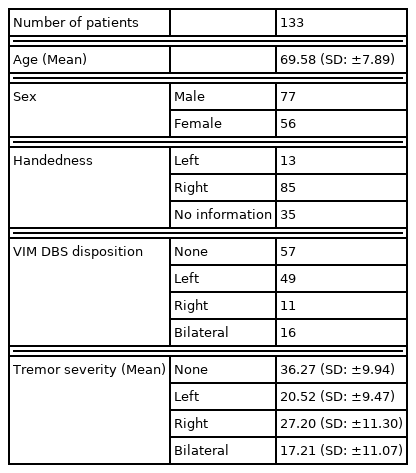

Participants included in this analysis provided informed consent and were enrolled in an IRB-approved database (INFORM). This is a retrospective study, and a chart review was conducted to identify all ET patients who completed speech and swallow evaluations before or after VIM DBS surgery between 2011 and 2016. Once participants were identified, demographic information, including age, sex, handedness, and tremor severity were collected (Table 1A). We also collected primary tremor site(s) (upper extremity, voice, and/or trunk) and DBS parameters including frequency (Hz) and amplitude (V) for the DBS groups (no DBS, left DBS, right DBS, and bilateral DBS; Table 1B).

Speech and swallow evaluation

Speech and swallowing evaluations were performed during the pre-surgical evaluation appointment (typically 1–3 months before surgery; no DBS group), or at least 6 months post-DBS surgery in DBS ON-state (after activation and optimization of stimulation settings) using our clinical protocol [17]. There were 6 evaluating speech-language clinicians with between 2 and 30 years of experience (Median: 8 years). Evaluations were performed independently, and any difficult or questionable evaluations were discussed at a monthly consensus meeting. The motor speech diagnosis (dysarthria type) was obtained from the speech evaluation note in the electronic medical record. As well, the severity ratings of individual speech subsystem components were recorded, including respiratory, laryngeal, velopharyngeal, orofacial, rate, and prosody (Table 2A). Severity was rated on a 0–7 ordinal scale, with 0 indicating normal function, and 7 profound dysfunction (anarthric) (Table 2B).

Swallowing evaluation was performed by the same clinicians that conducted the speech evaluations. The fluoroscopic swallow evaluations were completed using Varibar® Barium Contrast agents, with the patient seated in the lateral viewing plane. Patients were presented with 2 teaspoons of thin liquid barium (thin liquid barium sulfate for suspension (40% w/v after reconstitution)), 1 cup sip of thin liquid barium, 1 sequential (3 oz) of thin liquid barium, 1 teaspoon of pudding barium (pudding barium sulfate esophageal paste (40% w/v, 30% w/v)), 2 teddy-graham cookies coated with barium, and 1 cup sip of thin liquid barium. The worst Penetration-Aspiration (PA) score across all consistencies was recorded [18].

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS statistics 24 (SPSS Corp, Chicago, Ill, USA). The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis Test was used to investigate differences between DBS groups (none, left, right, bilateral) in motor speech ratings, and PA score. A corrected p-value for multiple comparisons of <0.0083 was considered statistically significant. Post-hoc analyses were completed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Finally, Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the type(s) of dysarthria present in the DBS groups.

RESULTS

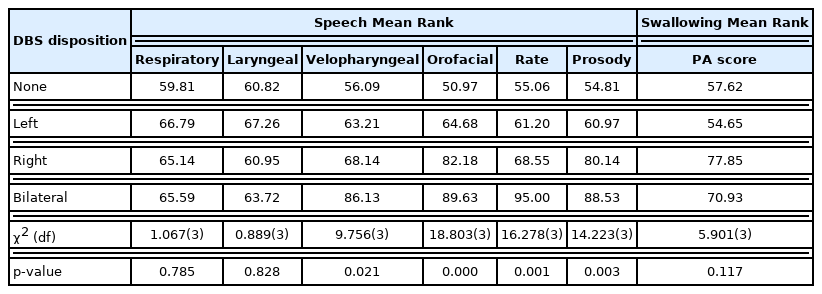

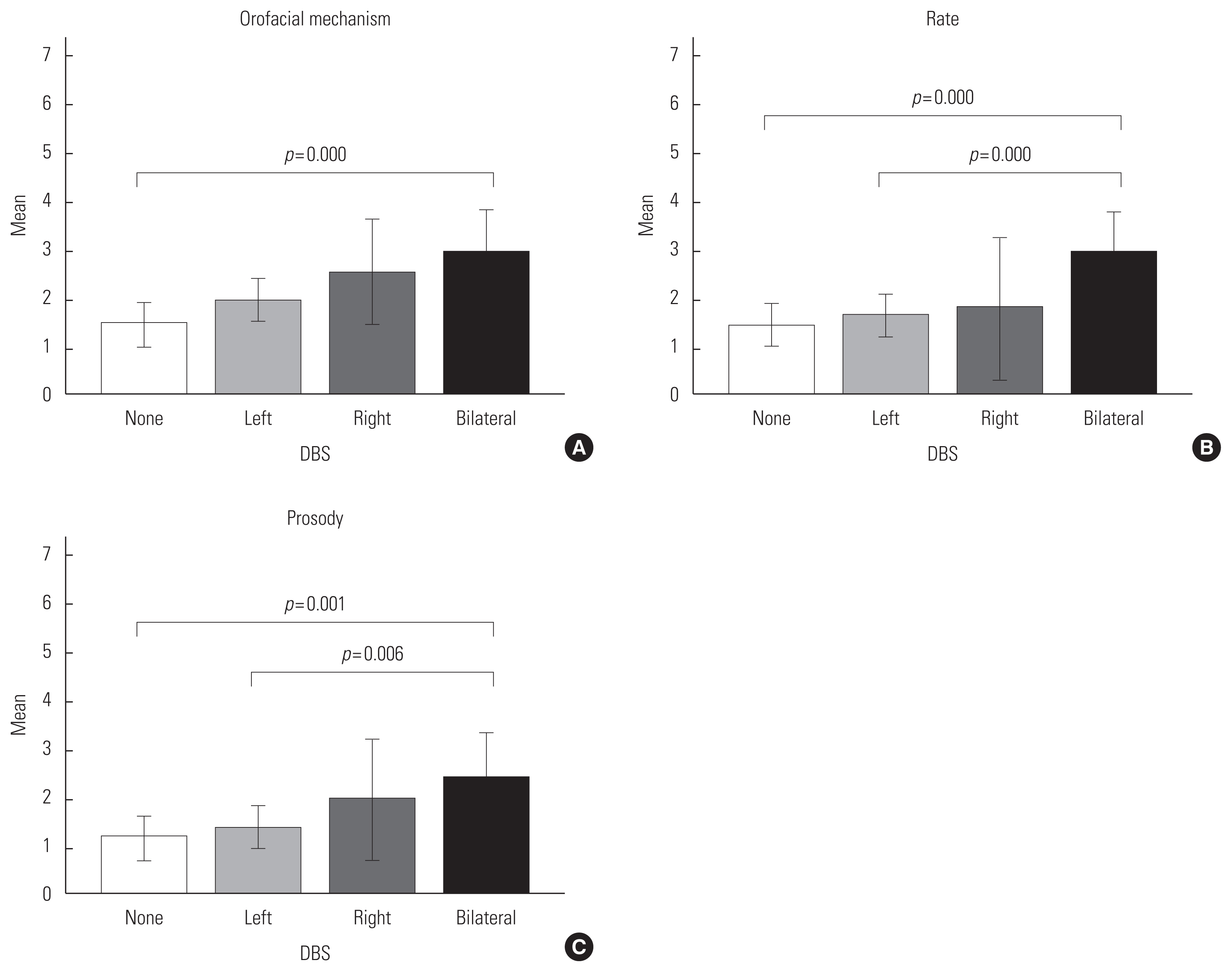

There were significant differences in several speech components, but not swallowing PA score, between the ET DBS groups. Specifically, the orofacial mechanism (p=0.000), rate (p=0.001), and prosody (p=0.003) domains were significantly different between groups (Table 3). Post hoc tests showed significant differences between the no DBS and bilateral DBS groups in orofacial mechanism (p=0.000) and in prosody (p=0.001). There was significant difference between left and bilateral DBS groups in prosody (p=0.006). Both the no DBS and bilateral DBS groups (p=0.000) and the left and bilateral DBS groups (p=0.000) showed significant differences in rate (Figure 1, Table 4). Investigation of the mean values shows that generally the bilateral group had higher (more severe) scores compared to the left, right, and no DBS groups (Figure 1).

Significant differences in speech and swallowing components: There were significant differences in several speech components, but not swallowing, between the ET DBS groups. Specifically, the orofacial mechanism (p=0.000), rate (p=0.001), and prosody (p=0.003) were significantly different between groups

Orofacial Mechanism, Rate, and Prosody by DBS disposition: (A) Oral mechanism has a significant difference between the none and bilateral groups (p=0.000); (B) Rate has significant differences between the none and bilateral groups (p=0.000), and between the left and bilateral groups (p= 0.000); (C) Prosody has a significant difference between the none and bilateral groups (p=0.001), and between the left and bilateral groups (p=0.006) (The error bars: 99% confidence intervals).

DBS group comparison in significant speech functions: There are significant differences between None-Bilateral group (p=0.000) in orofacial mechanism, None-Bilateral group (p=0.000) and Left-Bilateral group (p=0.000) in rate, and None-Bilateral group (p=0.001) and Left-Bilateral group (p=0.006) in prosody

Dysarthria types according to DBS disposition

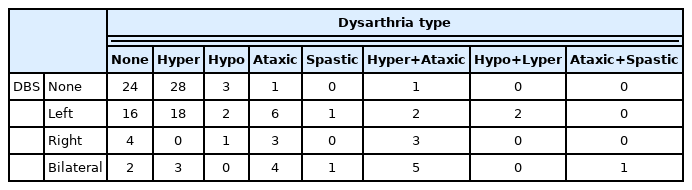

ET patients without VIM DBS, and those with only a unilateral DBS lead predominantly presented with either no dysarthria, or hyperkinetic dysarthria (vocal tremor). However, patients with bilateral VIM DBS had higher rates of dysarthria that included an ataxic component as shown in Table 5. The difference in dysarthria types was not significantly different between groups (p=0.448).

Dysarthria types by DBS disposition: ET patients without VIM DBS, and those with only a unilateral DBS lead predominantly presented with either no dysarthria, or hyperkinetic dysarthria. However, patients with bilateral VIM DBS had higher rates of dysarthria that included an ataxic component (ataxic component rate in each group: Without DBS group=3.50%; Left DBS group=17.02%; Right DBS group=54.55%; Bilateral DBS group=62.50%)

Swallowing functions before and after DBS surgery

Bilateral VIM DBS showed a trend towards worsening swallow function as compared to no DBS and left sided unilateral DBS groups. However, the difference in PA score (p=0.117) was not significantly different between groups (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The goal of the present study was to investigate the impact of VIM DBS on speech and swallowing functions in patients with ET based on retrospective data from four groups of patients with ET. Results showed that speech, but not swallowing, was significantly different between DBS groups. Specifically results show that bilateral VIM DBS is associated with more severe speech outcomes than unilateral DBS. The specific features of the speech evaluation that were significant different between DBS groups were articulatory precision (orofacial), speech rate, and prosody (Figure 1). Patients with bilateral DBS tended to have reduced articulatory precision accompanied by a slow, variable rate, dysprosody, and equal stress pattern.

While there are inconsistent research findings on speech function after VIM DBS in patients with ET, the current findings are consistent with those of Becker and colleagues [1,15] and Mücke et al. [11,15], who previously reported slow rate and/or low intelligibility in ET patients with VIM DBS. Together, these speech characteristics are most consistent with those seen in ataxic dysarthria [19].

The presence of ataxia is a documented side-effect of VIM DBS [11,16,20,21], and it is postulated that this relates to the spread of stimulation to other thalamic nuclei (including the ventrolateral nucleus important for relaying ascending information from the cerebellum to cortex), and consequently impacts the thalamo-cortical and cortico-ponto-cerebellar pathways [22–24]. The ventrolateral (VL) nucleus acts as a relay station between cerebellar fibers, the primary motor cortex and premotor cortex. Because of the proximity to the VIM nucleus, there may be spread of stimulation to the VL, disrupting communication between the cerebellar control circuit and the motor cortex (Figure 2). Since these are bilateral pathways, unilateral VIM DBS results in relatively preserved speech function because of the “intact” contralateral pathway, however, with bilateral VIM DBS this is not possible.

Cortico-ponto-cerebellar pathway: The presence of ataxia relates to the spread of stimulation to other thalamic nuclei (including the ventrolateral nucleus important for relaying ascending information from the cerebellum to cortex), and consequently impacts the thalamo-cortical and cortico-ponto-cerebellar pathways.

*VL: ventral lateral nucleus.

Interestingly, the results of the current study showed slight differences between left and right sided unilateral VIM DBS, with right VIM DBS associated with slightly worse speech function compared to left. While expressive and receptive language functions are predominately mediated by the left cerebral hemisphere, speech prosody is considered to be a largely right hemisphere function. Thus, it is possible that these results as they relate to dysprosody may reflect the importance of the right hemisphere to the prosodic contour of speech. This hypothesis should be explored with future prospective experimental studies.

The mechanisms of DBS are not completely understood, however, it is thought that stimulating the VIM modulates the irregular basal ganglia pattern into a more regular, stimulus-induced pattern that consequently reduces the tremor. Regarding speech, there does not appear to be as robust effect for ameliorating hyperkinetic speech characteristics [23,25]. There were not differences in the presence of vocal tremor between the study groups, indicating that the presence of unilateral or bilateral VIM DBS electrodes did not eliminate hyperkinetic components to dysarthria in this patient cohort.

Regarding swallowing, there were not significantly different differences in swallow safety (PA score) between groups. While swallowing difficulties are not common in ET, they can be present and are attributed to tremor in the trunk or head [26]. Thus, if these tremors are reduced or eliminated, it is reasonable to hypothesize that swallowing function may actually improve. However, VIM DBS does a relatively poorer job of ameliorating axial tremor as compared to appendicular tremor, so this may explain lack of impact (improvement) of DBS on swallowing function. Lapa et al. [16] identified the adverse effect of VIM DBS surgery on swallowing function using FEES. It is also possible that our metrics did not adequately capture swallowing function. Swallowing functions have been mostly investigated with small sample sizes comparing pre-and post-DBS conditions, making it difficult to better characterize the impact of both unilateral and bilateral VIM DBS on swallowing function. Thus, we only included PA score to generalize the implications for swallowing with a larger sample in this study. Our statistical analysis failed to identify differences in swallowing function, however the metric of swallowing safety, the PA score, may not have captured differences in swallowing efficiency or physiology. Future studies should include standardized metrics of swallow function, such as MBSImpTM, timing and kinematic measures in order to fully elucidate the impact of VIM DBS on swallowing function.

We identified speech and swallowing changes in the ET patient population after VIM DBS. However, because of the retrospective nature of the study, we were not able to look pre/post-operatively at the cohort and it was not possible to go back and re-assess the data to evaluate interrater variability. This study is limited by use of clinical evaluation results instead of carefully controlled, and validated measures of speech and swallowing. Also, this study only characterized DBS surgery impacts on speech and swallowing function with four grouping, and did not compare findings before and after surgery.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the current study indicate the presence of a detrimental effect for bilateral VIM DBS on speech function, specifically to the domains of articulatory precision (orofacial), rate, and prosody. While our statistical analysis failed to identify differences in swallowing function, this should be interpreted with caution, as the clinical swallow analysis may not have captured changes to specific functional or physiologic components of swallowing. While additional research is needed, speech-language clinicians should be aware of potential changes, and participate in the pre-operative counseling of ET patients regarding these potential impacts on speech and swallowing.

Notes

FUNDING

This project was supported by grants from the NIH NIDCD (R21DC014567) and NIH NICHD (R01HD091658) to Karen Hegland (PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.